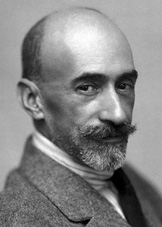

Benavente, Jacinto: Autumnal Roses (detail) (Rosas de otoño (detalle) in English)

Rosas de otoño (detalle) (Spanish)Comedia en tres actos

Personajes Isabel María Antonia Carmen Laura Josefina Luisa Gonzalo Pepe Ramón Manuel Adolfo Un Criado

ACTO PRIMERO Gabinete elegante.

ESCENA PRIMERA Gonzalo, un Criado y después Isabel. GONZALO.— (Al Criado.) A las siete lleva usted la ropa al Casino, y si ha venido alguna carta... ISABEL. — ¿Vas a salir? ¿Volverás pronto? GONZALO.— ¿Por qué? ISABEL. — ¡Qué memoria! ¿No recuerdas que hoy coen aquí Maria Antonia, Pepe y amigos?... GONZALO. — Es verdad. No me acordaba. ISABEL. — ¿Pensabas comer fuera de casa? GONZALO.— Sí, en el Casino, con Aguirre y con un soció suyo, para tratar de esos negocios de Bilbao. Pondré dos letras. (Al Criado.) Espere usted. (Se sienta a escribir.) ISABEL.- ¿Te contraría? GONZALO. — No. Siento no haberme acordado antes... Y que hoy no estoy de humor para recibir gente... SABEL. — Casi toda es de confianza. GONZALO.— ¿Quién viene? ISABEL. — Además de María Antonia y Pepe, Laura, Ramón y Carmen con la chica; Manolo Arenales, y, de más cumplido, los recién casados, el hijo de tu corresponsal y su mujer. En su obsequio es la comida. ¡Pero qué memoria la tuya! GONZALO. — ¡Ah, si..., el matrimonio joven!... ¡Cuánto siento! ISABEL.— Pues disimula el mal humor, porque los imeros días te desviviste por obsequiarlos, y extrañarán el cambio tan brusco. A mí no me son nada simpáticos; él parece tonto, y ella... ¡Qué sé yo! Muy atrevida…; por hacernos ver que domina el castellano, se expresa en unos términos... GONZALO. — ¿Puedes callarte? Me has equivocado dos veces. ISABEL. — ¡Ay! Perdona. ¿Por qué no lo has dicho antes? GONZALO.— (Al Criado.) Esta carta, al Casino. Y lleve usted la ropa; prepáremela usted en mi cuart (Sale el Criado.) ¿Y a qué hora es la comida? ISABEL. — Para las siete y media, media hora antes que de costumbre; también en obsequio a los de París; como allí se come temprano... Arenales se descolgará a las nueve, y la francesa tendrá motivo para decir que aquí estamos muy mal educados. GONZALO.— ¿Quién es la francesa? ISABEL. — La mujer de ese muchacho. ¡Qué pregunta! GONZALO. — Como no es francesa... Eso sí que es de mala educación, poner motes a la gente. Si sabes que es española...; porque haya vivido siempre en París. Es una muchacha muy agradable y muy inteligente. ISABEL. — Perdona, perdona si te he molestado. GONZALO. — No digas tonterías. ¡Siempre lo mismo! ISABEL. — ¡Siempre lo mismo! ¡Pobre de mí! GONZALO. — Ahora hazte la víctima. Eres insoportable. ISABEL. — ¡Gonzalo! Está visto que no puedo hablar. No puedo callar tampoco. GONZALO. — Prefiero que hables, que hables siempre y nunca con medias palabras ni con reticencias. ¿Si sabré yo por qué te molesta esa muchacha?Porque ya creíste también que me gusta; crees que me gustan todas las mujeres. ISABEL. — Todas, no. GONZALO. — Tendré que ser un grosero para que vivas tranquila; no podremos recibir más que a Laura…; es la única que te inspira confianza. ISABEL. — Sí, Laura; de ésa no te enamoras, es solo ella la que está enamorada de ti. GONZALO.— Una leyenda... ISABEL. — Que yo prefiero a muchas historias. GONZALO. — ¡Muchas historias! Don juan Tenorio. ¡Si conmigo no hay mujer segura!... No adviertes que te pones y me pones en ridículo con tus celos; debes pensar que ya no somos niños. Yo no lo era cuando nos casamos; viudo desde muy joven, con una hija ya mujer; de modo que no pudiste creer que buscaba en ti, como otros viudos con hijos, una institutriz de confianza. Si hubiera tenido ese corazón tan volandero y tan fácil que tú me otorgas, no hubiera vuelto a casarme. ¿Quién le obligaba? ISABEL. — Es que nunca reparaste en nada para conseguir lo que te propones. GONZALO.— ¿Y qué? ISABEL. — Conmigo no había otro medio. GONZALO. — Pero a ti te quedaba otro si creías eso; mandarme a paseo. ISABEL. — Creí que me querías. GONZALO. — ¡Que te quería! No te quiero, ¿verdad? ISABEL. — Sí me quieres; ¡es tan fácil quererme!... GONZALO. — ¡Qué bonito y qué simpático es el papel e víctima! ISABEL. — No lo sé: sé que es muy triste, y más triste procurar con todas mis fuerzas no parecerlo. Tienes una disculpa, la única. Haces el daño sin saber que lo haces. GONZALO. — Sí, acabaré por creerlo. Soy un monstruo, un tirano. El genio del mal. Este pobre y pacífico burgués, sólo preocupado de sus negocios, de su casa, de su mujer, de mi hija, mis únicos cariños. ISABEL. — De mí, no digo; sé a qué atenerme. ¿De tu hija? Nuestra; porque sabes que no la querría más si fuera también mía... ¿A que juzgas como de mí, que ebiendo ser muy dichosa se aficiona demasiado al papel de víctima? GONZALO. — ¿María Antonia? ¡Estaría gracioso! Se habrá contagiado... No, si tú eres capaz... ISABEL. — No, Gonzalo; no soy yo, no es ella; sois vosotros, los hombres, que sois como Dios os ha hecho, o el mundo en que vivimos, o..., ¡qué sé yo!, la ley que habéis hecho vosotros, tan tolerante para vuestras faltas como severa para las nuestras. GONZALO. — Vamos a elevar la discusión a principios filosóficos y sociales... ¡Ea!, voy a vestirme. No quiero ponerme de peor humor. ISABEL. — Está bien. ¿No quieres saber nada de hija? GONZALO. — Pero ¿qué voy a saber? Que está que quejosa de su marido, como tú lo estás siempre de mí, y con el mismo fundamento... ¡Pobre Pepe! ISABEL. — Conste que -María Antonia tiene razón, y conste que sabiéndolo yo, te lo digo a ti solo; a ella aunque tú creas lo contrario, le digo lo mismo que tú dices: que no tiene importancia; que Pepe no es mejor ni peor que otros maridos; que no debe estar triste ni considerarse desgraciada... GONZALO. — ¿Tú le dices eso a María Antonia? Me cuesta trabajo creerlo. ISABEL. — Sí, se lo digo y procuro convencerla; porque María Antonia no es como yo; es muy exaltada, no se resigna; además, no quiere a su marido como yo te quiero; se casó sin reflexionar, enamorada de otro hombre...

|

Autumnal Roses (detail) (English)COMEDY IN THREE ACTS

Characters Isabel Maria Antonia Carmen Latjra Josefina Luisa Gonzalo Pepe Ramon Manuel Adolphe A Servant

THE FIRST ACT Sahn in a house in Madrid, furnished with refinement and taste. I As the curtain rises, Gonzalo is speaking with a Servant. Isabel enters. Gonzalo. Have my clothes at the club before seven. Should any letters arrive… Isabel. Are you going out ? Do not be long. Gonzalo. How is that? Isabel. You are the most irresponsible man I ever saw. Have you forgotten that Maria Antonia and Pepe are coming to dinner? And we have asked a few friends. Gonzalo. Do you know, it had quite slipped my mind? Isabel. Did you plan to dine out? Gonzalo. Yes, at the club. I have some business with Aguirre and his partner in reference to that affair at Bilbao. I must drop him a line. [To the Servant] You may wait. [He seats himself and begins to write.] Isabel. I hope you are not disappointed ? Gonzalo. No, although I am sorry I did not think of it before. I am in no humor for company this evening. Isabel. We expect only a few — in fact, scarcely any one but the family. Gonzalo. Who is coming? Isabel. Maria Antonia and Pepe, Laura, Ramon and Carmen with their daughter, besides Manuel Arenales. I have asked your correspondent's son and his wife, the bride and groom, as well. The dinner is in their honor, so that makes it more formal. I am surprised that you should forget it. Gonzalo. The bride and groom? Ah, yes! I remember ... I am so sorry, Isabel. Perhaps you will conceal your feelings, as you almost prostrated yourself to entertain them when they first arrived in Madrid; the change would come as too much of a shock — although I never cared for them myself. He seems foolish, and she — well, she is too forward. To convince us that she talks Spanish, she employs the most objectionable language. Gonzalo. May I have a moment? I have made two slips already… Isabel. I beg your pardon. You should have said so. Gonzalo. [To the Servant] Take this letter to the club. Never mind the clothes. Lay them out in my room. [The Servant withdraws] At what hour do we have dinner? Isabel. At half after seven — half an hour earlier than usual, so as to accommodate the young Parisians. In Paris they dine early. When Arenales drops in at about nine, that French girl will say that all Spaniards have bad manners. Gonzalo. What French girl? Isabel. The bride. A foolish question to ask! Gonzalo. She is not French. Besides, I consider it bad taste to call people names. No one could be more thoroughly Spanish — she has lived in Paris all her life, so that I find her intelligent, indeed especially delightful. Isabel. I had no idea that you felt so strongly. Gonzalo. Nonsense. Do we have to go through this all over again? Isabel. All over again? How about me? How do you suppose I feel? Gonzalo. You are a martyr of course; this is intolerable. Isabel. Gonzalo, you are not willing to let me say a single word. You don't like it if I am silent, either. Gonzalo. No, I prefer to have you talk — talk all the time, only be direct about it; don't insinuate. I know why you don't like that girl: it is because you think I am fond of her; you think that I am in love with all women. Isabel. Not all women. Gonzalo. No doubt you would be happier if I possessed the manners of a boor. Laura is the only woman you are willing to receive in the house; in your eyes, apparently, she is perfectly safe. Isabel. You will never fall in love with Laura. She is too fond of you. Gonzalo. I seem to have heard that story before. Isabel. It is truer than most of your stories. Gonzalo. Yes, my stories! Don Juan Tenorio! No woman is safe in my hands. Don't you see that your jealousy only makes us both ridiculous? We are not children; I was not a child when I married you — I was a widower when I was a mere boy; I have a married daughter. Nobody imagines that I was looking for a nurse when I proposed to you, like most widowers who have children. If my heart had been so fickle and flighty, why should I have married again? What good would it have done me? Isabel. None; except that you hatl set your heart on it. Gonzalo. On what? Isabel. There was no other way with me. Gonzalo. You could have refused me if that was your opinion of me; you had another way. Isabel. I thought that you loved me. Gonzalo. Loved you? Don't I love you? Isabel. Yes, you do. It is very easy to love me. Gonzalo. Why are you so fascinated with the role of martyr? Do you think it becoming? Isabel. I don't know; it is very trying. The hardest thing about it is trying not to show how hard it is. Your only excuse is that you don't know how much you make me suffer. Gonzalo. Although some day I am likely to find out. I am a tyrant, a monster, an evil genius — I, a poor, inoffensive gentleman, who thinks of nothing but his business, his wife, his daughter, his home, who never cared for nor even dreamed of anything else! Isabel. As for myself, I say nothing, because I am used to it. But you owe something to your daughter — yes, our daughter — I love her as much as if she were mine. I suppose you think that she is wedded to the role of martyr like I am, when she has everything in the world to make her happy? Gonzalo. Maria Antonia? Never! That is, unless… But no, you would be incapable… Isabel. Yes, Gonzalo, and it is not her fault either; it is yours, her husband's — men's. You are as God made you, or else as opportunity has, or as bad as the law will allow, for you have made it yourselves. It is as lenient with your faults as it is intolerant of ours. Gonzalo. Are we elevating the discussion to a moral and philosophical plane? It is time to dress. I cannot afford to get into any worse humor. Isabel. You certainly cannot. Don't you care to hear about your daughter? Gonzalo. But what am I to hear? That she is jealous of her husband, as you are of me, and upon precisely the same grounds. I am sorry for poor Pepe. Isabel. However, Maria Antonia is right, and it is my duty to warn you. I talk to her exactly as you do to me, although you will never believe it; I tell her that it is of no consequence, that Pepe is neither better nor worse than other husbands; it is no disgrace and nothing to feel badly about, anyway. Gonzalo. Do you talk like that to Maria Antonia? It does seem incredible. Isabel. I not only talk to her, I convince her. Maria Antonia is not a woman of my disposition; she is excitable, her temperament is not one to resign itself. Besides, she does not love her husband as I do you. She was in love with another man when she married.

|

||||||||||||